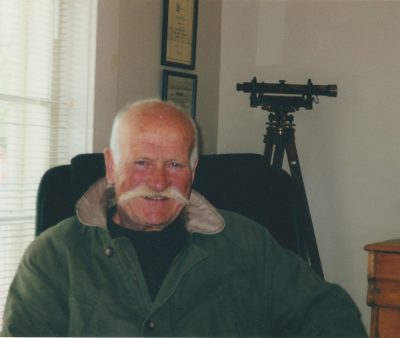

Sandy Martin

Un texte de Peter Turner

Paru dans le numéro Été/Summer 2019

Publié le : 7 juin 2019

Dernière mise à jour : 26 octobre 2020

Sandy Martin died last fall at the age of 87. Apart from the last couple of years, he spent his entire life at Elmsmead, the family farm at the top of the hill in Frost Village. After his family, his passions included: Jersey cows, personnel management, music and sugaring. He was born, the sixth of…

Sandy Martin died last fall at the age of 87. Apart from the last couple of years, he spent his entire life at Elmsmead, the family farm at the top of the hill in Frost Village. After his family, his passions included: Jersey cows, personnel management, music and sugaring.

He was born, the sixth of three boys and four girls on what was one of the last self-sufficient farms in the region. That’s to say: the family made most of their own clothes, Grandfather made the shoes, and they produced all of their food, other than staples. Sandy’s younger sister Rosemary, now a retired schoolteacher in Ontario, recalls “…all of us working together, pitching hay, milking cows and tapping trees. They were wonderful years.”

And the family made music together. The father, Gerald was on the cornet, which he played professionally, somebody or other was on the piano, and everybody sang. Sandy studied the trombone at the Montreal Conservatory. Music was central to his life. In his youth, he’d played for the Waterloo town band and in the Knowlton town band (as a ringer). For many years, he fronted a widely popular Bavarian dance band. At the mike, his bilingual energy was infectious. It is hard to imagine anybody else raising a room of staid judges and lawyers from their tables to dance with happy abandon at their annual Bar Association dinner. Later in life, he enjoyed playing the trombone or tuba with the Knowlton Harmony Band.

For several years, Sandy helped his father on his horse-drawn milk run. Six days a week they would trot down the hill through Frost Village, and on into Waterloo – delivering double on Saturdays. In his early twenties, Sandy took over the run on his own. Fridays would include a trip to the Bank of Montreal to deposit the weeks’ proceeds and later enjoy a beer or two with the bread-man. Lillianne Belanger was a teller at the bank. Sandy preferred to ignore shorter lines at the other tills so as to do his business with her.

When her brother told him that she would be at a dance on a Saturday night, Sandy attended and managed to get a dance with her. Lillianne was surprised to notice that he was carrying a flask in his breast pocket (“Cheaper than the bar,” he’d said). Nevertheless, she allowed him to walk her back to her parents’ house. On the steps, he asked if he might see her again. In hesitant English she replied, “I think I’d rather not, thank you.”

“Do you have you a good reason?” he asked.

“Yes, I have three,” she said, “You’re English, you’re Protestant, and you drink too much.”

Sandy replied, “Well then, we’ll fix all three.” And indeed, he did. He learned French, converted to Catholicism (“…because it was close enough to Anglican anyway,”) and reduced his partying sufficiently to get to the altar. He long maintained that, after having seen his deposits, Lillianne married him for his money!

They fixed up a little house on the farm, and had five remarkable children who were never quite sure whether they were anglophone or francophone. With the passing of Sandy’s parents, the family moved into the big house. Shortly thereafter, the milk run was sold to Chagnon Dairies. Sandy, in his forties, now needed more income to raise and educate his growing family.

Paige Thornton, who was the President of the Clairol operation in Knowlton (today’s Knowlton Packaging) was drawn to Sandy’s personality on the bandstand. They often chatted. One day Paige suggested that Sandy come to see him about a job. That led to his becoming Personnel Manager for a 400-employee plant. At night, he attended classes at the Bishop’s University School of Business.

It would not have been unusual for Sandy to arrive home from a band gig at 3:00 AM, tend to his milking three hours later, and arrive in Knowlton on time for work. He acquired notoriety as a man who could fall asleep anywhere and at any time – from a business meeting in the city to a social visit in a friend’s living room. “Like Judge’s nap,” he would maintain – “I might look like I’m gone, but I don’t miss a word.”

It soon became clear that there was no longer time for dairy farming. With immense sadness, Sandy cleaned up and brushed the 30-cow herd that was his pride and joy and trucked them over to Oley Young’s Auction barn. That night he slept with them. He cried as they were sold off the next day.

Most of those Clairol employees were from Brome County. Sandy Martin loved the work and the employees loved him. More importantly, they trusted him. He gave each of them the same deference and respect that he gave to the “big bosses” in Toronto and New York City. The pin stripe suits at HQ at 345 Park Avenue vied to sit next to him at lunch. “From the Wharton School of Business to the School of Frost Village – all the same to Sandy,” a friend said. The twinkle in his eye, his ready smile, and his generous wit, would draw people to him, whether at a business dinner in Toronto or at Sepp’s Beer Garden on a Friday afternoon.

Some thirteen years later, new management at Clairol brought in consultants from away. They had difficulty understanding Sandy’s lack of a formal Human Resources background. A short time later, he retired back to Elmsmead, and reconstituted the dairy herd with his son Peter.

Sandy Martin was happy in everything he did – except handyman stuff. That it was not his forte was a great source of amusement to his family. One of his friends gave him a “No tools required” plumbing repair kit for Christmas. After several hours of fruitless effort, it was flung into a distant snowbank followed by a brilliant string of oaths.

Into his eighties, he had the dreaded realization that the big house with its stairs was no longer going to work for him. His family gingerly persuaded him that a move in to a more efficient arrangement might be for the best. He was skeptical when Lillianne guided him into a light-filled, elevator-equipped third floor condominium on a small rise overlooking Waterloo. She soon realized he was happy when he went out onto the balcony and blasted his trade-mark moose call over the tranquil town. On many days, he went back to the farm to see where he might lend a hand. In sugaring season, his favourite time, he was there daily to supervise the boiling.

Today, Peter and his family show their Jerseys at Brome Fair. The Martin children and grandchildren number over 30. Every Christmas they gather at the farm. Now Peter, the eldest son, presides graciously over the family that was so ably nurtured by his parents.