Paulina Reynolds

Un texte de Heather Darch

Paru dans le numéro Hiver/Winter 2019

Publié le : 3 Décembre 2019

Dernière mise à jour : 22 octobre 2020

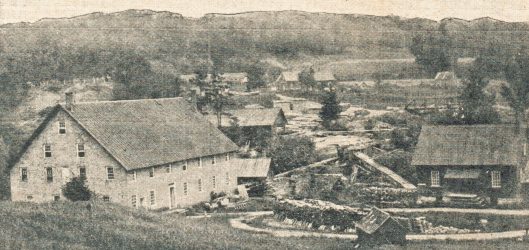

The village of Lagrange, also known as Hunter’s Mills, was at one time an active mill community. At its centre was the Lagrange Woollen Mill where wool was cleaned, carded, spun into yarn and woven and folded into cloth. It was known for producing « double and twist stripe wool cloth…wide flannels for sheeting…checked red and…

The village of Lagrange, also known as Hunter’s Mills, was at one time an active mill community. At its centre was the Lagrange Woollen Mill where wool was cleaned, carded, spun into yarn and woven and folded into cloth. It was known for producing « double and twist stripe wool cloth…wide flannels for sheeting…checked red and grey wool for shirting…and cloth for home trade. » Its beginnings as a commercial enterprise began in 1796 when Abram Lagrange (1769-1846) settled northwest of Frelighsburg and built a sawmill, a gristmill and a woollen mill and named the location Lagrange. In 1841, Abram allotted his mills to his four sons; Omie Lagrange (1815-1900) then 26 years old was to oversee the woollen mill.

This enterprising man can be found throughout Missisquoi’s historical records. He appears in muster rolls for the Frelighsburg Volunteers, the Frontier Mounted Police, and the Frontier Light Infantry during the Rebellion years of 1837-1839. Omie Lagrange is in business records purchasing and selling properties. He opened a post office where he was the self-appointed postmaster and he even established a store where customers evidently finished transactions with a shot of gin. Omie is also in notarial records for “protests” made against him and for grievances he held. While it is easy to see this busy man in the records, it is harder to see his wife Paulina and yet, she has an important place in Missisquoi County history.

Paulina Reynolds (1815-1904), daughter of Loyalists Benjamin Reynolds and Mary Freligh, married Omie Lagrange in Frelighsburg in 1840. Together they had four children, but in 1849, Omie left everything to make his fortune in the California gold rush. While he was away, Paulina carried on the business of running the woollen mill. This is extraordinary in a time when married women in particular, were not in leadership roles designated as men’s work.

Historically, woollen mills employed both men and women (and even children), with unequal pay. This allowed mill owners to help keep costs low to operate the water-powered looms and machines. If women worked outside of the home, they were employed in “acceptable female roles” as teachers, seamstresses, housekeepers, launderers and saleswomen. And yet, Paulina was taking care of the business as Omie looked for gold. In her capable hands, the mill prospered and successfully produced its blankets, flannels, and wool sheeting. The 1851 census indicates that the “Factory of cloth” produces $500 income per year profit with 12 persons employed. The census taker leaves no mark to indicate that Paulina was the boss.

In 1852, Omie is in El Dorado, California calling himself a “physician” and he reappears in the 1870 and 1881 census records in different locations in the state as a “starch manufacturer,” not a gold miner. In 1865, he returned to Lagrange briefly and turned the mill into a knitting mill to make men’s underwear for the Union Army during the Civil War. When the war ended that same year, the orders were cancelled leaving the mill without a market. There is no way of knowing what Paulina must have thought of this disruptive plan.

By 1870, Omie had returned to California, but not before he sold the mill to his son-in-law Nelson Hunter who converted the mill back into a woollen cloth mill; renaming it Hunter’s Mill. Paulina is with Omie in 1870 in San José working as a house keeper, but the 1880 census of Missisquoi County reveals that she had returned to Frelighsburg and lived with the Hunter’s. Perhaps she returned to care for grandchildren or because her son was a “spinner” in the mill. Maybe she returned so she could advise Nelson on how to run the business!

In 1880, Omie lived in Monterey, California and on an 1892 voting form, he calls himself a “mining expert.” On May 30, 1900 his name appears in an obituary notice in Salinas, California. Under the heading “Death of a Pioneer,” Omie was touted as a pioneer of the state and prominently known in San Francisco and Los Angles. Obviously Omie was travelling and seeking gold between census reports. Paulina must have reunited with Omie sometime in the 1890s as she is buried beside him. There is no notice about her life accomplishments, but we can remember her as a pioneer in women’s history in her own right and as the first female miller in Missisquoi County.

Heather Darch

Musée Missisquoi Museum

2 rue River, Stanbridge East Qc J0J 2H0

(450) 248-3153 info@missisquoimuseum.ca

Sources:

The Missiskoui Standard, July 10 1838; Frelighsburg Church of England, Holy Trinity 1808-1879: folio 3; Quebec, Canada, Vital and Church Records (Drouin Collection), 1621-1968; British Army and Canadian Militia Muster Rolls and Pay Lists, 1795-1850; Missisquoi County Historical Society 7th Annual Report 1961; 1870 Census: San Jose, Santa Clara, California; Page: 191B; Family History Library Film: 545587; 1881 Census St Armand East, Missisquoi, Quebec; Roll: C_13204; Page: 15; Family No: 64; 1851Census St Armand, Missisquoi County, Canada East (Quebec); Schedule: A; Roll: C_1127; Page: 11; Line: 33; California Voter Registers 1892 CSL #20; FHL # 976929