The Laundryman

Un texte de Heather Darch

Paru dans le numéro Printemps/Spring 2020

Publié le : 21 février 2020

Dernière mise à jour : 22 octobre 2020

On August 16, 1896 a small classified ad in the Bedford Times stated that: “Mr. Wah Lee opens his laundry in the old cheese manufacturer, close to the covered bridge (61 rue du Pont).” This unassuming advertisement is easy to miss amidst the larger ads, but it is far more important because behind its simplicity,…

On August 16, 1896 a small classified ad in the Bedford Times stated that: “Mr. Wah Lee opens his laundry in the old cheese manufacturer, close to the covered bridge (61 rue du Pont).” This unassuming advertisement is easy to miss amidst the larger ads, but it is far more important because behind its simplicity, lies a story of hardship and sacrifice, endurance and survival. It represents a significant part of Quebec’s history and Canada’s story as a whole.

Fleeing the political instability and poverty of mainland China, the first wave of Chinese people, mostly young men, came to “Gold Mountain,” the Chinese name for Canada, beginning in the 1880s. Like other immigrants, they came to find a better life. Over 15,000 Chinese labourers built the western section of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR); over 1,000 of these men died in the process.

Shortly after the completion of the railway, the Federal government under Sir John A. Macdonald imposed a discriminatory head tax against all Chinese settlers to discourage immigration. In 1885, the tax was $50; by 1903, it was an astonishing $500. No other immigrants paid this tax yet people like Mr. Lee of Bedford were forced to comply. In 1923, Canada levied the Chinese Exclusion Act to prevent Chinese people from entering Canada. This effectively isolated the community and divided families. Known as “Gold Mountain widows,” women left behind in China had to look after the household, serve their extended families, raise the children and eke out a subsistence living, all the while hoping for little remittances from their husbands in Canada. In 1947, the exclusion law was repealed, but by then many families had been separated for over 20 years. Immigration for Chinese people remained controlled until 1967.

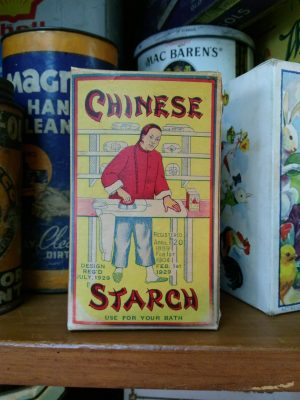

Socio-economic discrimination and racial intolerance forced Chinese people to earn a living in the lowest economic niches in society. Many found work in hand laundries; all work, from washing to ironing, pressing and packaging, was done by hand. In 1915, Quebec enforced a tax on Chinese laundries and laundrymen were fined or jailed for refusing to pay. Shockingly, it was only lifted in 1984.

The exclusion years, 1923 to 1947, were a period of resistance and struggle for the Chinese community in Quebec, but they joined the war effort to raise money and many enlisted in the Canadian armed forces. After the war, they joined the grass roots campaigns across the country to demand citizenship and the right to vote.

With the passing of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms in 1982, Chinese Canadians felt that it was time for Canada to redress the 62 years of legislated discrimination. It took 22 more years for the redress campaign to overcome the government’s unsympathetic position of “no apology/no compensation,” but in 2006, Chinese people finally won an apology and partial redress for the few hundred surviving head tax payers and their spouses. The apology did not extend to the children separated from their fathers even though some still suffer from the emotional consequences. Decades of state racism touched people in profound and lasting ways.

After 24 years, Mr. Lee’s laundry closed in 1920. An announcement in Le Canada Français stated that: “Charles-Edouard Dery of the house Monty & Jetté is pleased to announce that he has resumed all the old and new practices of our late Chinese man, who left us for China these last days.” The Canadian Census records fail to indicate the fate of Wah Lee and while many men share the same name in the records, it is impossible to know which one is Mr. Lee of Bedford. If he stayed in Quebec past 1923, he would have been separated from his family in China; perhaps for the rest of his life.

The Chinese brought their regional, cultural, culinary and historical traditions to Quebec society and Quebec’s Chinese community today is diverse in both regional and national backgrounds. At 100,000 people, Montreal’s community is the fourth largest in Canada.

Heather Darch

Musée Missisquoi Museum

2 rue River, Stanbridge East Qc J0J 2H0

(450) 248-3153 info@missisquoimuseum.ca

Read other articles by Heather Darch

Sources:

The Bedford Times, August 16, 1896; Not Welcome Anymore, cbc.ca/archives/entry/chinese-immigration-not-welcome-anymore; William Ging Wee Dere, Being Chinese in Canada; The Struggle for Identity, Redress and Belonging; For further reading: bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/discover/immigration/history-ethnic-cultural/early-chinese-canadians/Pages/research-resources.aspx?wbdisable=true