First Love

Un texte de Peter Turner

Paru dans le numéro Automne/Fall 2017

Publié le : 21 septembre 2017

Dernière mise à jour : 26 octobre 2020

Aunt Lilias had few happy days during her 58-year marriage to Delbert Wright. She’d often told Charlie, her favourite nephew, “In the back seat, on the way to the church, Daddy leaned over and whispered, ‘It’s not too late to turn this car around.’ Oh I know it will hurt for a time, but it…

Aunt Lilias had few happy days during her 58-year marriage to Delbert Wright. She’d often told Charlie, her favourite nephew, “In the back seat, on the way to the church, Daddy leaned over and whispered, ‘It’s not too late to turn this car around.’ Oh I know it will hurt for a time, but it won’t hurt for a lifetime.”

Well, it did hurt very nearly for a lifetime. Lilias had no bank account of her own, Delbert undermined her every friendship, was persistently jealous of imagined boyfriends, and never trusted her driving. And there were no children.

“You didn’t divorce then Charlie. In those days we just stuck it out. I confess I was not sad when he dropped dead in the shower.” In fact, she had gone across to her neighbour’s apartment, joyfully thrown her hands in the air, and exclaimed, “He’s dead!”

Soon after she was widowed her long dormant sense of humour awakened. She was of medium height, fit, and remarkably well-preserved. In the old age home, Lilias had been able to afford to put two rooms together, to give her a sitting room. With a sheet of plywood over the bathtub, she converted the second bathroom into a well-stocked bar. She was easily the most popular girl in the place.

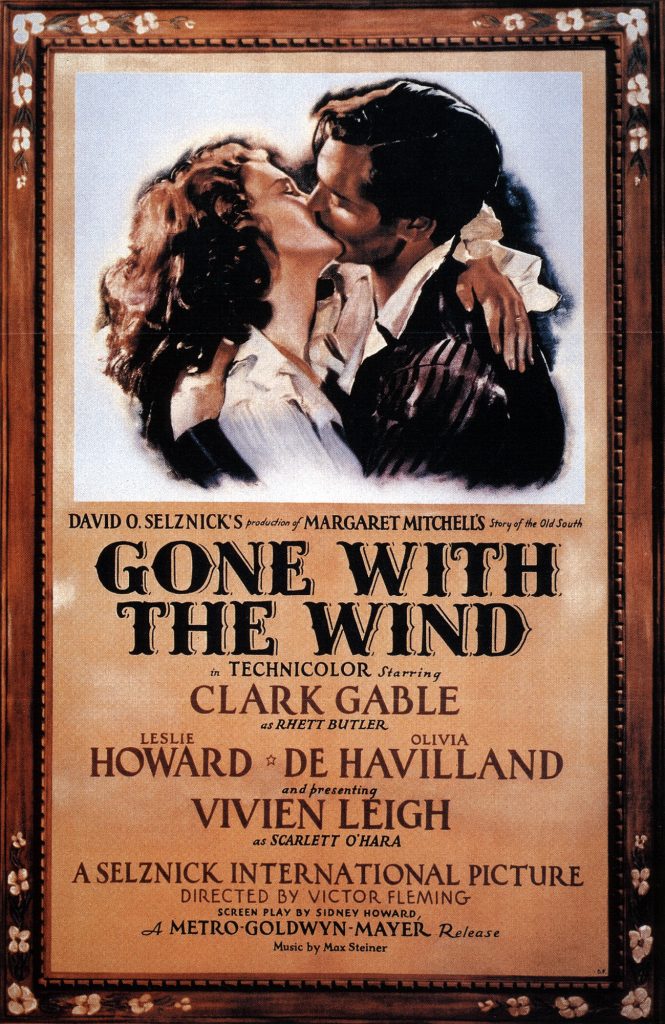

Around Christmas the name “Raymond Miller” started to pop up. “Oh, he was such fun Charlie.” Months later, after two rye and gingers, she allowed that they had seen Gone With the Wind together. Another time, she glowed in a reminiscence of dancing to Guy Lombardo.

Finally, when he was driving her home after her 80th birthday champagne party, she spilled it all. She and Ray had been at Bishop’s University after the war. He was a “Cardboard Box” Miller from Toronto. “Biggest cardboard box factory in the country, but Charlie, you’d never have guessed that he had any more do-re-mi than the rest of us.”

He had been a year ahead of her. In her freshman year, he’d given her his Frothblowers drinking club pin at the Football Formal dance. They’d seen each other almost every day for two years when he started talking about the beautiful children they might have one day.

Back in Stanton, Lil’s family loved Raymond Miller. He helped her father with the double windows, unloaded groceries for Mrs. Jones, and played crib with the family. He was ideal in every way. The Jones were anxious that she meet his family up in Ontario, but the time never seemed just right. In the year of Raymond’s graduation it was arranged that she would take the train to Toronto and stay with the Millers through New Years’ Day. She got a new valise, and spent money on clothes that her father could ill afford. As a house gift brought along a gallon of her family’s best maple syrup.

Raymond met her at Union Station and they drove, through winding roads, to an imposing brick house in Rosedale. Mrs. Miller answered the door. She was tall, angular, and handsome in a severe grey suit, with a silk scarf, and a coloured wool band in her hair. Lil felt as if she should curtsey. Raymond gently took Lil’s arm and led her in, “At last Mother, here is my Lilias.” Lil offered forth the can of maple syrup. Mrs. Miller said, “Why thank you dear, how charming.” She was dismayed to observe that Raymond’s familiar confident manner had vanished.

“I knew right then that we were done, Charlie. Mrs. Miller said all the nice things, but there was not a pinprick of warmth in that house. When Mr. Miller got home from work, a big fat bald man in a vest, he looked me over without a hint of a smile, and disappeared alone into his study for a drink. Dinner was a nightmare. There were different forks and spoons and all, clusters of water and wine glasses and all manner of odd silver objects; it was like a jigsaw puzzle. When Mrs. Miller asked, ‘Would you like some applesauce, dear. I said, “No thank you.” Then she said, “Well then could you please pass it along to me?” God, it was right smack dab in front of me Charlie. I couldn’t talk. As for Raymond, he was just plain frozen. After dinner he was hangdog, not the same person. I was heartsick and couldn’t hide it. Next day I said I was so sorry to feel so unwell, and took the bus home.’

‘Back at school, we tried to pick up where we had left off, but, like father might say, “we were flatter than a plate of piss.” Delbert, was a day boy from Sherbrooke. He was sweet and quiet and he’d been sniffing around since first year. We were married that October and he came to work here, as an assistant comptroller at the furniture factory.’

‘That was a lovely party Charlie, please stay a bit.’

They sat side by side on her old love seat. ‘Raymond has been mentioned in the Bishop’s News. Last year there was a picture of him with his son, at his grandson’s graduation. “Three Generations,” it said. He’s lived in Boston for years. A dentist. Oh damn it Charlie best tell you the truth. I phone him last week, got the number from the Alumnae Directory. His wife answered. I must say she was not very congenial. She asked who I was. I panicked—said I was a doctor. Stupid, I know. She said, “No you are not. I know you are that “lovely” old Lilias woman up in Quebec. The one he’s always talking about.” And she hung up.’

‘Next day I got a call from his nurse. She said she’d overheard our conversation and said Raymond did indeed often mention me. She went on to tell me that this Rachel woman moved in last year and is determined to be his third wife. She won’t let anyone near him, not even his children.’

Lil put her hand on Charlie’s knee, ‘Oh how I’d like to talk to him Charlie. Would you try for me?’ She pointed to a number scrawled in pencil across a whole page in her address book. He dialled and turned on the speakerphone.

‘Yes, Hello,’ came a harsh female voice. Lil grimaced and waved her hands.

‘Oh hello.’

‘Who are you?’

Well, I’m Charlie Owen, an old curling friend of Ray from Bishop’s days. Has he mentioned me? Just wanted to wish him well.”

Lil leaned forward.

“No sir, you are not an old Bishop’s friend. You’re phoning for her. I know. Raymond does not want to talk to her. He’s had another stroke, he’s been on a respirator for years and he’s diabetic. Would you please, for the love of God, leave us alone?”

A faint voice in the background said, “Whom did he say he was?”

“Oh just some makeup name Ray, Charlie Owens or something”

“Really, old Charlie! My goodness. Pass him over!”

“Hello Charlie, grand to hear from you, how have you been keeping?”

Lil grabbed the phone and turned towards the wall, she was blushing — “Oh Raymond dear, your voice hasn’t changed.”

Raymond responded, “Well yes Charlie, what a grand idea. I would love to come to the homecoming in September… my nurse Jennifer will bring me. You could call her with the arrangements, ‘and he gave Jennifer’s cell number.

Charlie called the next day.’ You know Mr. England, your aunt has given Mr. Jones new energy. He’s so alive this morning. Full of beans. And he stood up to her today.”

For Homecoming day, Lil was wearing new tan slacks a white silk blouse and a fashionable purple cashmere cardigan with Ray’s Frothblower pin on it. When he saw her, Charlie said, “Aunt Lil you are hot.” As they drove over to the university, the bright blue sky stretched high above Mount Orford.

They met at noon, on the steps of the Old Library. That was where they had last seen each other. He was wearing his old curling sweater. They giggled when they saw each other, and then hugged for a long time. With damp eyes and self-conscious smiles, they toddled off towards the Homecoming lunch, through loud music, BBQ smoke, and crowds of noisy students with purple painted faces and beer cans in their hands. They forgot that they were pushing walkers. “They seem awfully rowdy Ray.” “Yes, my dear, those are called tailgate parties.” They were the oldest graduates present—he 62 years and Lilias, one year behind.

They said farewell, knee to knee in the old common room where they used to play bridge. At 5 PM they left for home—he to Boston, some five hours away, and Lilias, back to Stanton. As she got in the car, Lil said, “I think that was the happiest day of my life Charlie.” She was silent the rest of the way home.

Lil and Ray talked on the phone every day, until he died almost a year later. She sent flowers, “To dear Raymond, the love of my life.”