Seeing Flavia

Un texte de Heather Darch

Paru dans le numéro Été/Summer 2015

Publié le : 15 mai 2015

Dernière mise à jour : 3 novembre 2020

Her name was Flavia. She didn’t have a last name or at least no one bothered to use it. We don’t know her age, or if she was married or had children. We don’t know if she was born here, in Africa, the United States, or even England. We don’t know where or when she…

Her name was Flavia. She didn’t have a last name or at least no one bothered to use it. We don’t know her age, or if she was married or had children. We don’t know if she was born here, in Africa, the United States, or even England. We don’t know where or when she died.

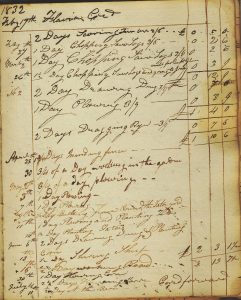

Her name does not appear in Census records, baptismal notices or death registers. She exists only in brief notations found in Philip Luke’s store ledger in 1832. Under her name were listed the items she was buying and how she paid for those goods over the course of one year. She is but a whisper in the past and had it not been for the ledger, no one today would have ever known that she existed. Flavia was a Black woman and while her story is unknown she had a role to play in Missisquoi County history.

It is believed that for a time, Philip Luke owned slaves, bringing them with him when he came to Missisquoi Bay following the American Revolution. Flavia might have been his slave for some part of her life but the fact that she is listed in the ledger under her own account suggests that she was free or an indentured servant while she lived in Philipsburg. Her name never appears before or after 1832. Did she pass away? Did she run away? Was she freed through the British Emancipation Act of 1833 which formally ended slavery in the Canadian provinces? Perhaps she simply moved to the growing Black community of Montreal.

With few exceptions, Luke’s accounts were maintained in the name of the male head of household, although other family members transacted business at the store. These household members were acting as agents of the patriarch, who was ultimately responsible for settling the account. Accounts were in the name of a female only when she was the head of household, as in the case of a widow. Single white women were listed by their full names when they worked for Mr. Luke. He repeatedly refers to Margaret Pulson working to pay off her debt; Sarah Rinehart is extended the same courtesy. Household chores were the mainstay of Cordilia Mining, Betsey Rinehart and Hannah Kreller. In all store ledgers in Philipsburg, Black individuals are only identified by their first names.

Flavia participated in “barter accounting” which was widespread in early Missisquoi, as it provided liquidity to the market in the absence of a sufficient supply of reliable money. Local trade used commodities such as cheese, eggs, honey, or woven cloth in place of money and kept trade flowing in the community. Flavia’s purchases reflected her life. She bought wood chips, corn, oats, hay, mutton, sheep skin, and mackerel. There are no feminine items such as ribbons, mirrors, and sewing accessories. She did buy a pair of shoes in February 1832. One could assume safely that Black women did not have many opportunities to buy luxury items. Whereas other customers routinely purchased coffee, tea, tobacco, sugar, salt and rum, only Flavia’s purchases of tobacco could be classed as an extravagance.

Interesting notations are made along with her acquisitions. She paid a monthly rent of 5 shillings for a roof over her head. She also rented the use of a cow so the hay, oats and corn were likely used for feed. The records do not indicate if she was using the milk to make cheese or butter to augment her income but these commodities were sold from Luke’s store. The maker of dairy products was not always indicated. Cheese was smoked for preservation and taste and this could explain Flavia’s purchase of wood chips.

What is most revealing is how Flavia paid for her purchases. From February to December 1832 she draws dung, chops cords of wood, cuts logs, ploughs, sows corn, mends fences, works the road, reaps rye, shaves sheep and cares for the “tator” yard. Flavia is also listed under the accounts of other landowners. She worked for them and paid off their debts in the store through an arrangement with Luke.

Her labour was not like that of white women. There were no reservations about Black women and hard labour. The experiences of enslaved women most certainly overlapped those of men. In the interest of extracting as much agricultural work from as many able- bodied slaves as possible, slave owners made no distinction between males and females.

Anti-slavery advocate Johann Martin Bolzius (1703-1765) observed that Black women harnessed oxen, ploughed, cut logs, hoed, picked crops, mined coal, dug canals and ditches, « grubbed » swamps and built railroads. « A good Negro woman has the same days’ work as the man in the planting and cultivating of the fields, » he wrote. Black women’s field work also served to separate them from white female labourers. In the US, 18th century Black women came to outnumber men as field workers. Black men became the beneficiaries of the growth in skilled labour and women increasingly performed the least desirable chores.

The lives of the early Loyalists and settlers were hard, tough even. This is common knowledge but nothing about the Black people of Missisquoi Bay is common knowledge. We know so little about them and yet there they were, like Flavia, lodged as firmly in our past as any other element of history.

Sources:

Philip Luke Account Book 1786-1838, Collections of the Missisquoi Historical Society;

The Slave Experience: Men, Women, & Gender, Jennifer Hallam www.pbs.org/wnet/slavery/experience/gender/history2.html; « Women’s Sweat: Gender and Agricultural Labour in the Atlantic World, » Jennifer L. Morgan p.147-150 in American Studies: An Anthology; ed. Codrina Cozma, « John Martin Bolzius and the Early Christian Opposition to Slavery in Georgia, » in « Georgia Historical Quarterly 88 (winter 2004): 457-76; « Black Then: Blacks and Montreal 1780s-1880s, » by Frank MacKey.

Musée Missisquoi Museum

2 rue River, Stanbridge East Qc J0J 2H0

(450) 248-3153