Into the Fold

Un texte de Heather Darch

Paru dans le numéro Hiver/Winter 2022-2023

Publié le : 14 novembre 2022

Dernière mise à jour : 14 novembre 2022

Slavery, while limited in St. Armand, was an ugly part of Missisquoi’s history. Abolitionists like Reverend Stewart and members of his congregation helped to bring it to a close.

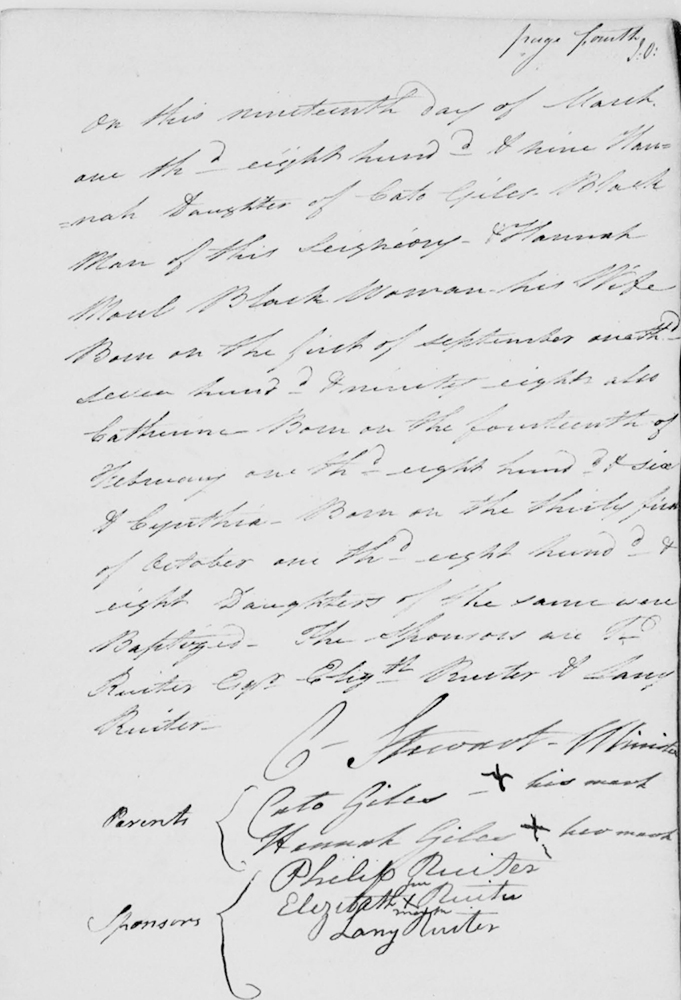

Sunday, March 19, 1809, was a day of celebration for the Anglican church congregation in the seigneury of St. Armand West (Philipsburg), Quebec. On this day, the Reverend Charles James Stewart (1775-1837), conducted a wedding service for one couple and the sacrament of baptism for two infants. He also baptized three little girls from the same family. This was not an unusual practice in the late 19th century which saw the growing appearance of ‘family baptisms.’ What was extraordinary about this service was that the girls were Black.

Standing before Reverend Stewart were “Cato Giles, Black man of this seigneury and Hannah Moul, Black woman and his wife,” along with their daughters Hannah, Catherine, and Cynthia. Not only were these Black children baptized into a white congregation, their “sponsors,” were Loyalist entrepreneur Philip Ruiter (1766-1820), his mother Elizabeth Best (1747-1816) and his niece Magdalena “Leny” Ruiter (1790-1860).

While not identified by a surname, the likelihood that Cato Giles had once been a slave in the community is suggested in the Last Will and Testament of Loyalist Jacob Best (1716-1794/95) of St. Armand dated February 14, 1794:

Also I give my Nigro Cato, full and free liberty to Live with any of my Own Children, Or with any of my Grant Children, to keep his Own wearing Aparel, and what Ever he Owns, without, he, or She, with whom Soever, of Own, or Grant Child, Cato Chuses to live, paying no money for Cato, but in Case Cato will not Stay with One of my Own or Grant Children, Cato is to find a Master to Buy him, and the Money is to be Devited Equealy among my Children.

Jacob Best chose not to free his slave before he died. And if this is indeed Cato Giles, it raises the possibility that he was perhaps purchased, that is freed, by Philip Ruiter (a nephew of Jacob Best). Or simply emancipated because Jacob Best’s son Hermanus, and other family members, were not interested in keeping him enslaved. Historian Frank Mackey determines that slavery was ‘done,’ in colonial Quebec, by about 1800. Long before it was officially over when the British Parliament abolished it throughout the Empire in 1834.

Cato and Hannah’s free status is supported by the fact that throughout Philip Ruiter’s store/inn ledger, he often mentions them working for him, purchasing goods and receiving payment for work completed. Hannah in particular is routinely owed money for her spinning. Their comings and goings in Ruiter’s business are not the actions of people who were owned by another.

Similarly, other people identified as Black also conduct themselves as free citizens. Albeit not on an equal social footing as their white neighbours. Mr. Ruiter forgoes using surnames and identifies people by their skin colour. Morris Emery is called “Morris the Blackman” for example. He sleeps and eats at the inn. He purchases goods like violin strings and works, probably as a musician, to pay his debts. While there is obvious discrimination in using colour and not surnames, in Ruiter’s Inn there is opportunity to be found.

Ruiter and Reverend Stewart were part of the growing abolitionist movement in the Anglican Church. Stewart’s political orientation was shaped directly by his sister, Lady Catherine Graham (1765-1836). She introduced him to England’s eminent evangelicals and wealthy humanitarians including the leading abolitionist William Wilberforce (1759–1833) who challenged the attitudes of the elite by advocating for the end of slavery.

In 1807, Parliament abolished the slave trade and while slavery “did not glide, neatly and nobly, to a halt,” it was the beginning of the end. Just seven months later, the young Scottish aristocrat Stewart arrived at Quebec; bringing his evangelical and anti-slavery teachings with him when he was appointed to the seigneury of St. Armand in 1809.

The Giles family eventually moved to the growing Black community in Montreal. Here they were members of the St. Gabriel Presbyterian Church congregation. Scant details of their lives can be found, but in the 1819 church records, middle daughter Catherine died at age 14 and oldest daughter Hannah married George Williams in December that same year. On the same day, they also baptized their son George Williams Jr. who was born in November. Within a few short months Hannah and Cato grieved the loss of a daughter, rejoiced in the happiness of another and celebrated the arrival of their first grandchild.

Sadly, less than a year later, Hannah Moul died on July 5, 1820, in St. Jean-sur-Richelieu and was buried in the church yard of St. James Anglican Church. In November, 22-year-old Hannah Giles Williams, was buried in the same graveyard with her little son George Jr.

A paradoxical relationship existed between churches and slavery, but the church was an important institution for Black people; providing spiritual care, education and the social and economic organization necessary for building communities. Slavery, while limited in St. Armand, was an ugly part of Missisquoi’s history. Abolitionists like Reverend Stewart and members of his congregation helped to bring it to a close.

Heather Darch

Sources:

Saint-Armand-Ouest Anglican Church, 1809-1899, BAnQ Sherbrooke, Fonds Cour supérieure. District judiciaire de Bedford. État civil, (05S,CE502,S48). https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/3974385?docref=rcb-btjacyuA2AkqnFe0kQ

Frank Mackey, “Done with Slavery: The Black Fact in Montreal 1760-1840,” McGill-Queens University Press, 2010.

William Wilberforce https://www.christianitytoday.com/history/people/activists/william-wilberforce.html

Charles James Stewart, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/stewart_charles_james_7E.html

Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec; Montréal, Quebec, Canada; Collection: Fonds Cour Supérieure. District judiciaire de Montréal. Cote CN601. Greffes de notaires, 1648-1967.; District: Montréal; Title: Chaboillez, Louis (1787-1801) Best, Jacob, Last Will and Testament, BANQ notary L. Chaboillez, no. 1340, 11 March 1795.

Transcription of the Last Will and Testament of Jacob Best, by Albert Smith http://www.uelac.org/Loyalist-Info/extras/Best-Jacob/Jacob-Best-Sr-will-by-Albert-Smith.pdf

Philip Ruiter Ledgers, 1799-1811, Private collection, Courtesy: Robert Galbraith & Phyllis Montgomery

Death and burial of Catherine Giles August 18 and August 21, 1819 https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/4441602?docref=6Cj8_Hy5_dYOg2QjcERZ0A

Wedding of Hannah Giles and George Williams December 6, 1819 and Baptism of George Williams Jr. born November 6, 1819, baptized December 4, 1819. https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/4441602?docref=MXy34wOYkNvDlKpsPsd1Mw

Death and burial of Hannah Giles July 5, 1820. St. James Anglican Church, Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu. Institut Généalogique Drouin; Montreal, Quebec, Canada; Drouin Collection; Author: Gabriel Drouin, comp. From Ancestry.ca

Death and burial of Hannah Williams and son George Williams Jr., November 29, 1820. St. James Anglican Church, Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu. Institut Généalogique Drouin; Montreal, Quebec, Canada; Drouin Collection; Author: Gabriel Drouin, comp. From Ancestry.ca