The Bugler’s Coat

Un texte de Heather Darch

Paru dans le numéro Hiver/Winter 2020-2021

Publié le : 24 novembre 2020

Dernière mise à jour : 7 Décembre 2020

A khaki woollen jacket with red trim, gold buttons and fringed epaulets stands out in the Missisquoi Museum collection.

A khaki woollen jacket with red trim, gold buttons and fringed epaulets stands out in the Missisquoi Museum collection. In tidy script found on the underside of one of the epaulets its owner is revealed to be “Frank F. Soule, Charles City, Iowa, Solo B b cornet, 1st Brigade Band.” This petite jacket is from the American Civil War and Frank Soule was part of a camp band.

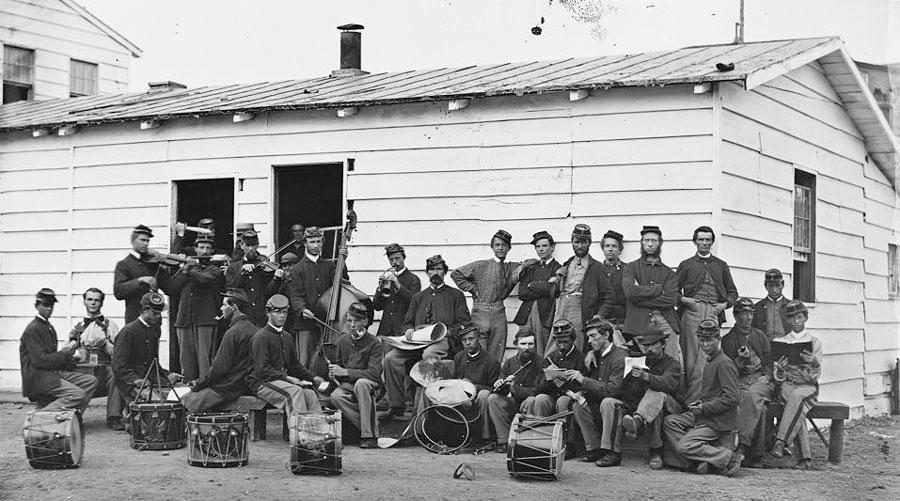

Within months of the start of the Civil War, Congress authorized the creation of Regimental bands for the Regular Army. The order entitled two field musicians (buglers or fifes and drummers) per company of soldiers and a band of 16-24 musicians for each regiment. This led to the formation of hundreds of bands and the enlistment of thousands of musicians whose duties were to provide music for the Army. Confederate General Robert E. Lee himself said “I don’t believe we can have an army without music.”

Both Union and Confederate officers encouraged the formation of camp bands to keep morale and spirits high among their troops. Professional musician Patrick S. Gilmore enlisted as a band leader in the 24th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry. His celebrated band consisted of “sixty-eight pieces,” including twenty drummers and twelve buglers. They played “in camp” and followed the regiment into the field to inspire soldiers to stand their ground. Gilmore’s own song “When Johnny Comes Marching Home Again” is still well-known today.

Confederate cavalry commander Major General James “Jeb” Stuart (1833-1864) was also a proponent of music in the camps. During the Battle of Fredericksburg (1862) the armies settled down on either side of the Rappahannock River. At night the camp bands could be heard playing; each taking turns to perform their favourite songs. One evening, the Union band played “Home Sweet Home” and General Stuart encouraged his band to play the same tune in response. Men on both sides of the river could be heard singing.

At the Battle of Gettysburg (1863), J. A. Leinbach, leader of the 26th North Carolina Regiment band, stated that “about 6 o’clock in the morning, the bands of the 26th and 11th North Carolina regiments played together for some time… Our playing seemed to do the men good, for they cheered us lustily.” A British observer, J. L. Freemantle, poised in a tree near Lee’s headquarters on Seminary Ridge also heard music. “When the cannonade was at its height,” he reported “a Confederate band of music… began to play polkas and waltzes which sounded very curious accompanied by the hissing and bursting of shells.”

From marching music to hymns, music moved the armies through their daily activities, revived morale and defused tensions. Musicians were assigned additional, often dangerous duties of equal importance too. They frequently found themselves assisting the wounded, fulfilling courier or reconnaissance duties and engaging in combat.

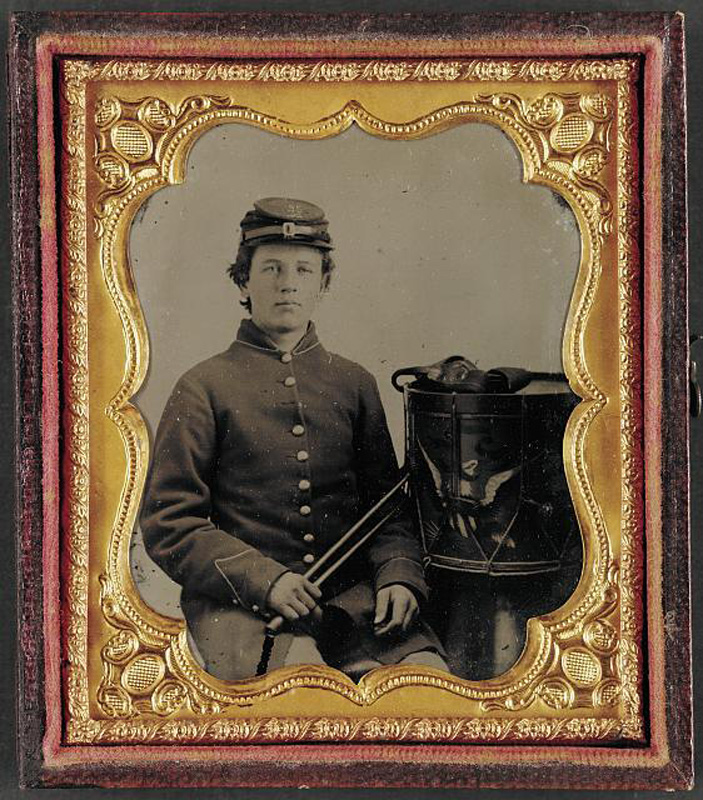

Although the minimum age for enlistment was 18, boys as young as age 12 were allowed to enlist as musicians. Frank Soule was part of the 44th Regiment Iowa Volunteer Infantry. The 44th Regiment served in the Union army and was one of scores of regiments that were raised in 1864 as “Hundred Days Men;” an effort to augment existing manpower for an all-out push to end the war within 100 days. Frank’s own days were numbered however, as he was “mustered out” for being “too young.” He must have served just long enough to obtain his band jacket.

It is a mystery how this boy’s coat came to Missisquoi County. The donor, missing the hidden inscription, thought it belonged to a Frank Soule from Franklin, Vermont who also served the Union army. It may have been passed along through Soule relatives on both sides of the border. In any case, the bugler’s jacket represents an important aspect of the Civil War.

Musée Missisquoi Museum, Stanbridge East

450 248-3153

info@missisquoimuseum.ca

missisquoimuseum.ca