A Bee in his Bonnet

Un texte de Heather Darch

Paru dans le numéro Été/Summer 2019

Publié le : 4 juin 2019

Dernière mise à jour : 22 octobre 2020

When we read through our splendid Le Tour and other local papers published in the Townships today, it might come as a surprise to know that at one time our newspapers were used for heated political debates and cutting verbal attacks. Besides providing space for obituaries and marriage announcements, community events, goods for sale, and…

When we read through our splendid Le Tour and other local papers published in the Townships today, it might come as a surprise to know that at one time our newspapers were used for heated political debates and cutting verbal attacks. Besides providing space for obituaries and marriage announcements, community events, goods for sale, and general news, the earliest newspapers in Missisquoi County were platforms for the political opinions of their editors. In fact, the words of a former editor of one Missisquoi paper were so inflammatory that he was accused of burning the parliament buildings in Montreal in 1849.

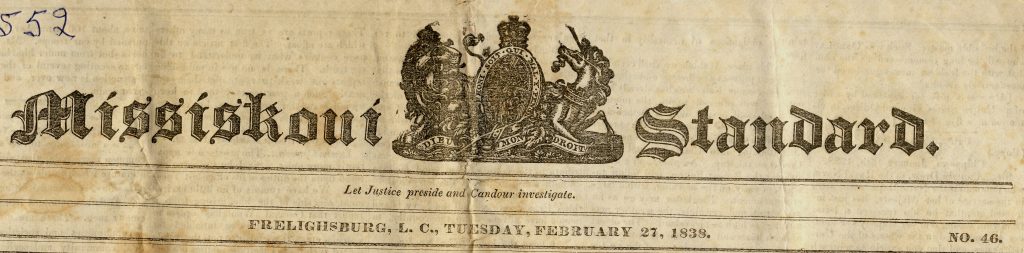

Scottish-born James Moir Ferres arrived in Quebec in 1833. At age 21, he came to Frelighsburg to fill the position of head master at the Frelighsburg Academy. By 1835, Ferres and Joseph Gilman established a weekly newspaper called the Missiskuoi Standard and Farmers’ Advocate. From this stage, Ferres expressed his conservative political opinions and feuded with other editors during the political upheavals that erupted into the Patriote Rebellion of 1837-1838. Of the young Mr. Ferres someone observed that, “He seemed only to think of how he could best damage or destroy.” Ferres’s anti-reform voice help to fuel the pro-government cause in Missisquoi to the point that one historian refers to Ferres as a “rabid Francophobe Scot.”

Ferres’s first target was the pro-Patriote newspaper The Missiskoui Post and Canada Record established in 1834 in Stanbridge East under its liberal editor Hiram J. Thomas. The paper ceased publication when the office was ransacked, the press was thrown into the mill pond and Thomas fled to Vermont disguised as a woman.

To counter the influence of the conservatives in Frelighsburg, a second Pro-Patriote newspaper called the Township Reformer appeared in Stanbridge East in 1836. It was edited by reform leader Elkanah Phelps. Stirring words from Mr. Phelps roused the citizens of Stanbridge East to hold a parade of over 1,000 Patriote supporters with the famous Patriote leader Thomas Storrow Brown leading the procession. This paper’s press was also destroyed and publication stopped after the outbreak of rebellion in November 1837.

Until his departure from the Missiskoui Standard in December 1836, Ferres was relentless in his anti-Patriote stand and urged the citizens of Missisquoi County to reject the “despotism of a few.” He became the editor for the Montreal Herald and in 1844, Ferres was appointed revenue inspector for Montreal, a job created especially for him by James Smith, the new Tory member of the Executive Council from Missisquoi. Ferres’s opponents considered this cronyism and “a vile political job.” The position ended abruptly with the formation of responsible government under Louis-Hippolyte Lafontaine and Robert Baldwin in 1848.

In December 1848, Ferres was hired as the editor of the Montreal Gazette, where he immediately took the lead in the conservative business community against the “madness of Free Trade.” He was also aggressively anti-French Canadian over the Rebellion Losses Bill which compensated Patriote supporters for property damages; ignoring the fact that English-speakers were also reimbursed.

His fractious words in the Gazette contributed to the general Tory agitation in Montreal and the consequent burning of the parliament buildings in April 1849. Throughout the previous winter, Ferres had condemned the bill as “a nefarious attempt at robbery of the Anglo-Saxon population” and his overheated rhetoric influenced a mob to march on the parliament and burn it to the ground. In the aftermath of the destruction, Ferres was among those arrested for arson. He was released on bail but the case never came to trial.

Ferres remained editor of the Montreal Gazette until 1854 and entered parliament as a Tory from Missisquoi-East. In his position on the Board of Inspectors of Asylums and Prisons, he championed prison reform. In 1869, he became warden of the Kingston Penitentiary; a position he held until his death a year later.

Ferres made many enemies throughout his public life; not the least of which were the English and French-speaking supporters of the Patriote cause in Missisquoi. It can be argued however that his fight to preserve the authority of the Crown, helped to advance the political education of citizens and engage people living in the small communities of Missisquoi fully in the political debates of Quebec.

Heather Darch