Coming Up Short

Un texte de Heather Darch

Paru dans le numéro Été/Summer 2023

Publié le : 5 juin 2023

Dernière mise à jour : 5 juin 2023

From 1798 to 1804, missionaries from the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel (SPG), came to St. Armand and quickly left again. John Doty, Robert Quirk Short, James Tunstall, and Charles Caleb Cotton.

Bishop Jacob Mountain had a problem. He had too many parishes and not enough Anglican priests. The good people of the seigneury of St. Armand at Missisquoi Bay said they would welcome a priest in a promise-filled letter to the bishop dated 1799. One seigneur, Thomas Dunn, pledged 200 acres of land for a glebe and others promised land sufficient for two churches. The letter even boasted that 1,500 people “… many of them of the Church of England, and most of them well affected towards it and disposed to unite with it,” were prepared to financially support a member of the clergy. Problem solved – or so the bishop thought.

From 1798 to 1804, missionaries from the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel (SPG), came to St. Armand and quickly left again. John Doty, Robert Quirk Short, James Tunstall, and Charles Caleb Cotton, each made a hasty retreat because “everything was so unfavourable, they left in despair.” Reverend Cotton reported to the bishop that the “indifferent” community “had not set aside even a room for divine service; they refused to give anything toward the support of a clergyman; and even on Christmas, when the whole strength of the congregation might be expected to assemble, there were only six persons present…” Of these early disgruntled priests, Robert Quirk Short left the least impression. “How long he stayed, or what were the extent and effects of his labours, there are no records to show.”

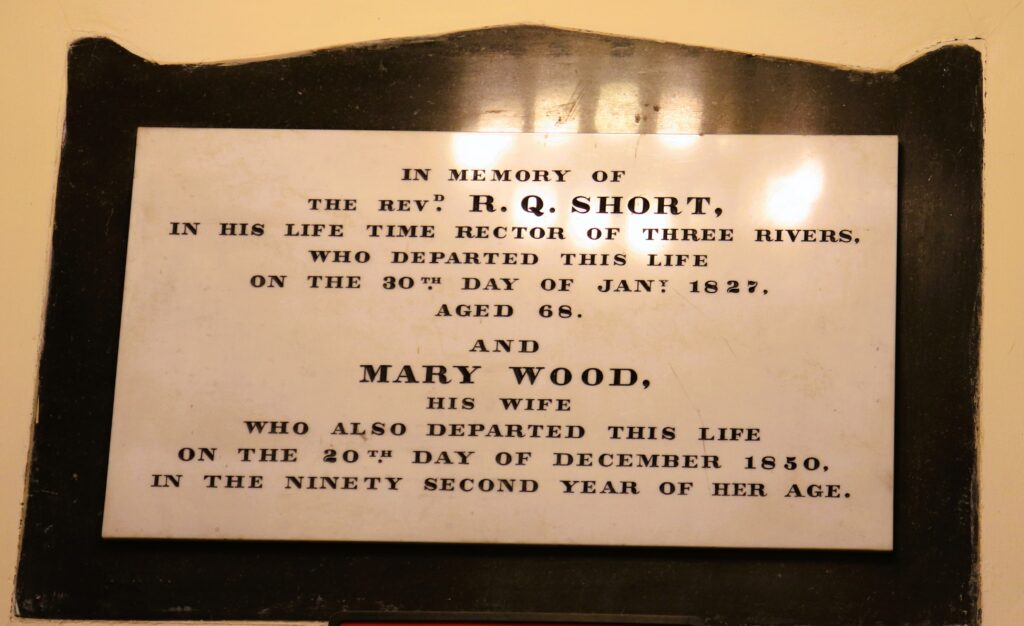

In 1787, Oxford educated Robert Quirk Short (1760-1827) was ordained a priest in the Church of England. Nine years later, he and his wife Mary Wood (1759-1850) and their children moved from Sommerset, England to Cataraqui (Kingston, Ont.). A 1797 report to Bishop Mountain stated that “Revd. R.Q. Short was practicing medicine, having recently arrived in the province with a wife and seven children without obtaining employment.» The report also claimed that Short had a “quick temper and harsh language” which made him “unsuitable for appointment.” Short himself wrote to the bishop requesting a pastoral charge, but Mountain was not impressed by his letter, concluding that Short was truly a man who “lacked both education and sense.” By 1800 however, he accepted Short as a missionary. The SPG, which would have to pay part of the salary, strongly objected, but Mountain’s need for priests prevailed.

While Short lost no time in coming to St. Armand, he departed within the year. On January 1st, 1801, he was already in Trois-Rivières as the priest for the St. James the Apostle Anglican Church. This congregation was also struggling and if the bishop thought that Short could turn the situation around, he was to be disappointed. Fifteen years later, Short revealed that the members were unable to contribute “a single farthing” to his living. In 1820, it was “yet without chalice or flagon, and could afford to build neither a church nor a parsonage.” There was no glebe land and there had been no donations for the poor.

Mr. Short had numerous conflicts with his parishioners too. People complained of Short’s inattentiveness, his refusal to bury a “dissenter’s” (Presbyterian) child, and his fees as “extortion.” In Short’s defence, similar complaints were common about the clergy who served the Anglican Church in this time period. Even Priest Cotton failed to visit parishioners and refused to bury a Presbyterian on the orders of the bishop.

In 1808, Short tried to obtain an ensign’s commission for his son only to be refused. One historian surmised that this was because of the “scandal in connection with Short’s marriage.” A cryptic accusation to be sure.

It wasn’t all bad though. People recalled that Short was “… amiable, a good conversationalist, … a man of the world, and a favourite in the intellectual society who enjoyed themselves … cultivating flower gardens, planting trees, dining in company, holding musical evenings, dances, and picnics.” Short also had a love of spectacle. Summoning his congregation for a demonstration of his own flying machine, he madly flapped its wings as he rose a few feet in the air only to tumble down amidst their applause. He also supported the endeavours of the Hart family in their struggles for Jewish civil and social liberties. These events did not diminish the esteem in which Mr. Short was held, but neither did the stories endear him to his bishop. A flying priest indeed!

In 1823, funds were provided for the renovation of the church and parsonage. Unfortunately for Short, he had little time to enjoy these improvements. He died in 1827 at age 68. The cemetery where he was buried lies under the road near the church. Today, the church building is being transformed into a centre for the performing arts. Reverend Short likely would have enjoyed this alteration. For a man who was but a brief notation in Missisquoi’s past, he certainly left an impression.

Heather Darch

Sources:

George H. Montgomery, Missisquoi Bay (Philipsburg, Que.) 1950. https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/2636119

Cyrus Thomas, Contributions to the history of the Eastern Townships, 1866.

Benjamin Sulte, Mélanges historiques ed. Gérard Malchelosse (21v., Montréal, 1918–34), 21: 56–61. https://digital.library.yorku.ca/yul-960863/m%C3%A9langes-historiques-%C3%A9tudes-%C3%A9parses-et-in%C3%A9dites-de-benjamin-sulte#page/8/mode/2up

Bulletin des recherches historiques : bulletin d’archéologie, d’histoire, de biographie, de numismatique, etc. /, août 1902, août https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/2657022