Words, and More Words

Un texte de Jay Sames

Paru dans le numéro Printemps/Spring 2019

Publié le : 26 février 2019

Dernière mise à jour : 3 novembre 2020

I’m a guy who looks up words as I read, and tries to remember them. Books I own are filled with scribbled definitions in the margins. It’s interesting to return to a book years later to notice what easy words I didn’t know then, and what I’d still have to look up now. In a…

I’m a guy who looks up words as I read, and tries to remember them. Books I own are filled with scribbled definitions in the margins. It’s interesting to return to a book years later to notice what easy words I didn’t know then, and what I’d still have to look up now.

In a trilogy from the 1930s, Studs Lonigan by James T. Farrell, I found molly-coddle, crepuscular and cur defined, as well as a lot of sexual and racial slang. In a book about “The Great Game”, I found foolscap, cerulean and memsahib. When did I not know them? While I often don’t remember words I look up, sometimes I surprise myself.

In the 1980s, I used an unabridged Webster’s New 20th Century Dictionary, 2nd Ed., and even though it was 2100 pages, I would lay it open on my lap when I read certain things. I remember distinctly—while watching something English I’d taped from Masterpiece Theatre—looking up yeomanry, which took a while because I didn’t know how to spell it!

Later that decade I was tested by The Johnson O’Connor Research Foundation, Inc.[1] Johnson O’Connor had begun in 1922 as a department of General Electric tasked with matching applicants to jobs. In their then 65 years of research—now 97 years!—they’d concluded that most aptitudes are innate and unchanging, except for vocabulary. Vocabulary should improve naturally as you age but can be also improved systematically. Their theory: new words near the frontier of your established vocabulary are easiest to learn and remember.

Even words you think you know might only come into focus much later. When I went to Johnson O’Connor, I lived in a townhouse in Wilmington, DE. But only last month, while reading Anthony Trollope’s The Way We Live Now—a novel about 1870s England—did I really understand the concept, origin and conferred status of having a townhouse in addition to your country estate.

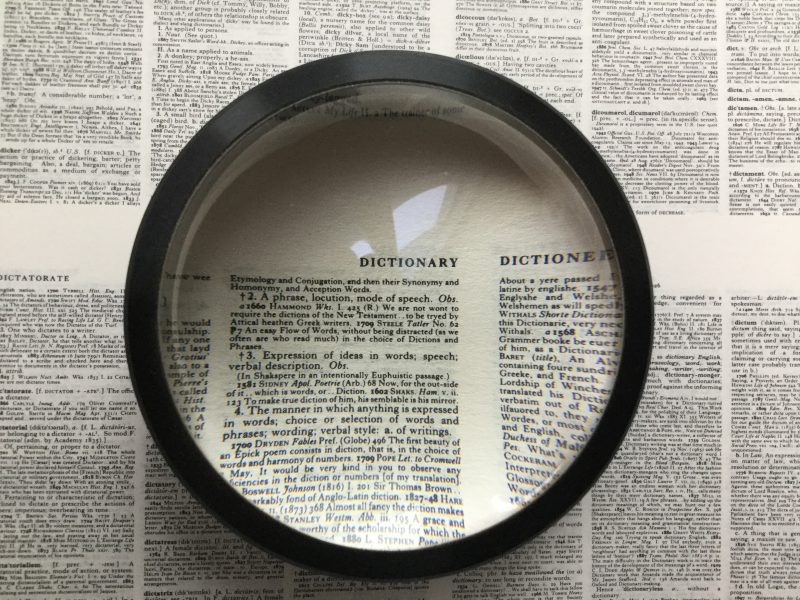

In the 1990s, I bought my OED, the Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed., in its “compact edition”. It was not abbreviated at all, but was “reduced micro-graphically” such that on each of the 2370 onion-skin pages were pictured nine original pages of the 20-odd-volume set, the words tiny. It came with a purpose-built magnifying glass to read them. It is not something that you can lay open on your lap, but I love it!

With the age of wifi, and Kindles and iPads, I’ve become a bit lazy, letting Google define and look up. But I still use my Webster’s and my OED.[2]

My pet peeve is when people use similar words incorrectly. Get thee to a dictionary! For example—this is your homework—look up and distinguish allusion, illusion and elusion. Also reluctant and reticent.

Just yesterday I looked up pettitoes (pig’s trotters) and somerset (only an English corruption of somersault, from French, nothing to do with Somerset County in southwest England). And I learned that the first definition of liaison is a thickening agent used in cooking, the adhesion aspect being what unites all other definitions.

When did I last surprise myself? In December, a friend texted me the word climacteric, and attached a Christian Science Monitor article.[3] As I often do, I tried to define it freestyle, in a quick return text before looking it up. You can judge how well I did by reading the article. I wrote:

“Climacteric comes from the Greek. The Greeks had an every-7-years thing describing a human’s lifetime, where 2 of them, 14 years, were when big changes were expected. Around your mid-60s was the ‘grand climacteric’, which I forget exactly, but poetically it meant that you’d reached/achieved great wisdom, eminence gris. I should look it up. When I knew it, I felt that I experienced those big changes at about the prescribed ages.”

We all learn more words as we age, mostly because we want to distinguish things and concepts more finely. As for me, approaching my grand climacteric, instead of feeling wise or learned, I feel there is so much more to learn. I’ll stay close to my dictionary.

Jay Sames

jay.sames@gmail.com

[1] See www.jocrf.org

[2] The OED is online now—kept current as they develop their 3rd edition—but it’s only available by subscription, too pricey for me.

[3] www.csmonitor.com/The-Culture/In-a-Word/2018/1213/A-Renaissance-fruit-has-its-climacteric-moment