Mrs. Brunner’s Work

Un texte de Heather Darch

Paru dans le numéro Hiver/Winter 2024-25

Publié le : 6 novembre 2024

Dernière mise à jour : 13 novembre 2024

The work of women in settlement history matters as the sensibilities and experiences of men give only half of the story.

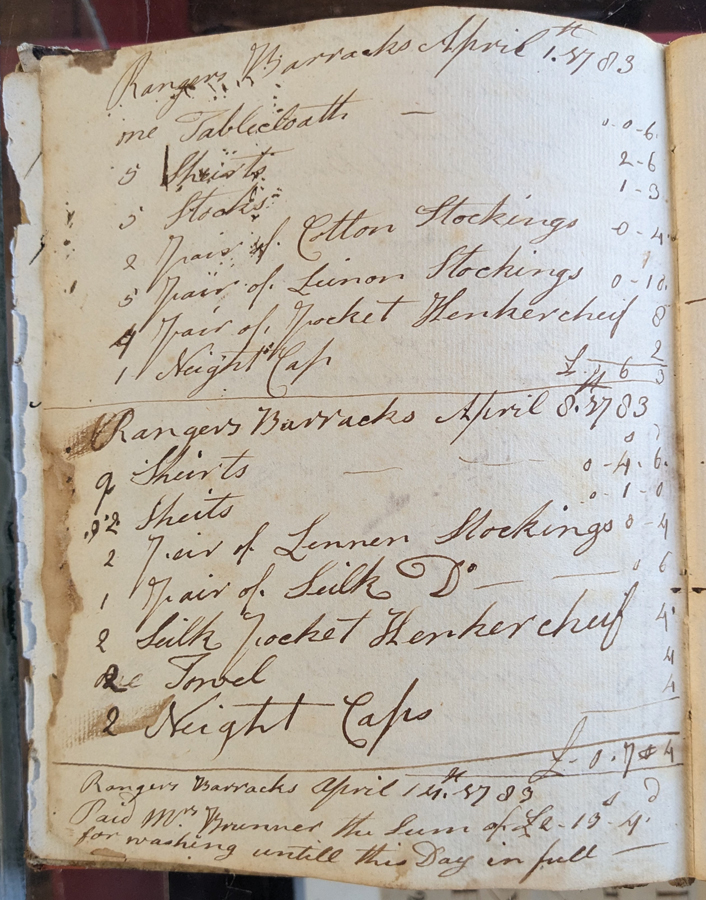

Tuesday was laundry day for Mrs. Brunner. On April 1st 1783, she washed a tablecloth, shirts, socks, linen and silk stockings, 9 pairs of pocket handkerchiefs and one nightcap. One week later, she did it again. But this time she washed 9 shirts, 9 sheets, two towels and two nightcaps. For her labour, she was paid the modest sum of 13 shillings and 4 pence. Her labour was for the men of the “Ranger Barracks,” at Fort Niagara. The remarkable notation of her work was recorded on the last pages of a ledger owned by Loyalist Captain Philip Luke. Three years later, on June 29, 1786, he recorded his first entry for his new supply store at Saint Armand, Missisquoi Bay.

Most business practices of women in early records were not recorded except perhaps in account books. When extra wages were required, especially during periods of men’s unemployment or absence during warfare, women’s paid labour was crucial to the family’s survival. Married women often marketed their domestic skills. And, by their own agency, played a central role in the economy of their households and in their communities. Mrs. Brunner’s work likely gave her a much-needed source of income to sustain her family during and immediately after the American Revolutionary War.

The work of a laundress or washerwoman, was labour intensive. But it was an activity that could be conducted from the home. Or perhaps in the case of Mrs. Brunner, at a British Army encampment. Normally, laundry was carried out over the course of 4 or 5 days in a weekly cycle. The basic elements included a fire and space to manipulate the vast tubs of boiling water and a wooden battledore, also called a posh or dolly, to stir and beat the laundry until it released its dirt. Washing also entailed the heavy job of wringing out wet clothes.

The laundress also made her own supplies. Besides hauling water and chopping wood for the fire, she made lye soap from ashes and salt. She also prepared “chamber bleach” from urine, which had to be collected from chamber pots and exposed to the air for several weeks to create a strong ammonia to whiten clothes. Her stain removers included pearl ash, vinegar, lemon juice, ox gall and “smalt” made from finely ground cobalt blue glass or indigo dye. Homemade wheat or potato starch was added to everyday clothing. But rice starch was preferred by the military as it created a sheen to the garments.

Laundry was either hung on clotheslines or laid on the grass to dry and further whiten in the sun. The laundress then used a mangle that was heated and rolled across carefully folded items of washing. Finishing irons would smooth remaining wrinkles.

Mrs. Brunner worked throughout 1783 until June 1784. Among the usual items of clothing, she also washed coverlets, curtains, waistcoats and calico coats throughout that year. Philip Luke’s last entry on June 7th 1784 states that he paid Mrs. Brunner “one pound eight shillings New York currency in full.”

In 1783, just as the war was ending, Luke was at Fort Niagara “destitute, of money and clothes and support,” and “drawing rations” serving with Butler’s Rangers (Capt. George Dame’s Company). Six full companies of Loyalist Rangers were assembled at Fort Niagara to receive support. They were housed in log barracks on the west side of the Niagara River. A Jacob Brunner was also a soldier with Butler’s Rangers (Capt. William Caldwell’s Company) and on a 1783 Provision List, he is recorded along with his wife Hannah Brunner and their sons Henry and Peter. A tentative guess is that Jacob Brunner’s wife Hannah may be the laundress of the ledger.

Philip Luke also faithfully recorded the names of women working in his business at Missisquoi Bay; both their debts owing and the payments made to them. Wages were routinely owed to women employed in his store and in his gardens and fields including Black women like Flavia and Lucia.

The work of Mrs. Brunner highlights what was certainly a vital role for her family and in the market economy of military camps. The work of women in settlement history matters as the sensibilities and experiences of men give only half of the story.

Heather Darch

Sources:

Philip Luke Store Ledger 1783-1838, Missisquoi Historical Society collections

Philip Ruiter Store Ledger, 1799-1800, Phyllis Montgomery collections; copy accessed at the Missisquoi Historical Society

The Loyalists, Pioneers and Settlers of the West, UELAC https://uelac.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Loyalists-Pioneers-and-Settlers-of-the-West.pdf

Loyalist Claims, 1776–1835. AO 12–13. The National Archives of the United Kingdom, Kew, Surrey, England. Ancestry.ca

Patricia E. Malcolmson, Laundresses and the Laundry Trade in Victorian England, Victorian Studies, Vol. 24, No.4 (Summer, 1981)

Michael Olmert, Laundries: Largest Buildings in the Eighteenth Century Backyard https://research.colonialwilliamsburg.org/Foundation/journal/Autumn09/laundries.cfm

Lieutenant Colonel William A. Smy, “An Annotated Nominal Roll of Butler’s Rangers, 1777-1784. “Friends of the Loyalist Collection at Brock University, Welland, Ont., 2004. Thank you, Horst Dresler for this source.

Norman K. Crowder, Early Ontario Settlers, A Source Book, Genealogical Publishing Co. Inc., Baltimore, Maryland, 1993.

Ernest Alexander Cruikshank, The Story of Butler’s Rangers and the Settlement of Niagara, Welland, Ontario: Lundy’s Lane Historical Society, 1893. Project Gutenberg Canada ebook #319.