“When Death Says Come”

Un texte de Heather Darch

Paru dans le numéro Été/Summer 2022

Publié le : 1 juin 2022

Dernière mise à jour : 1 juin 2022

Even in the late 19th century, it is estimated that a third to a half of all live births in Canada ended in death before the age of five. These calculations of child death probability were even greater for Black, urban and poor children.

The numerous gravestones of children found in the heritage cemeteries of the Eastern Townships are heartbreaking reminders of how often death came to the youngest members of a community. Marking the fleeting lives of children with enduring monuments upon their graves became a particularly significant task for families.

It is estimated that one quarter of all infants in 18th century Quebec did not live to see their first birthday and that nearly half died before they were 10 years old. These early years were perilous and, unfortunately, it was hardly better a century later. If a child could make it to 15 years of age in the early 19th century, there was a greater likelihood of living a full life ; bearing in mind that in the 1850s, life expectancy at birth was 43 years, roughly half of what it is today.

Even in the late 19th century, it is estimated that a third to a half of all live births in Canada ended in death before the age of five. These calculations of child death probability were even greater for Black, urban and poor children. The Krans Cemetery, located in the village of St. Armand, Quebec, has a gravestone that serves as a sad reminder of the fragility of childhood and the sorrow that parents faced with the loss of their children.

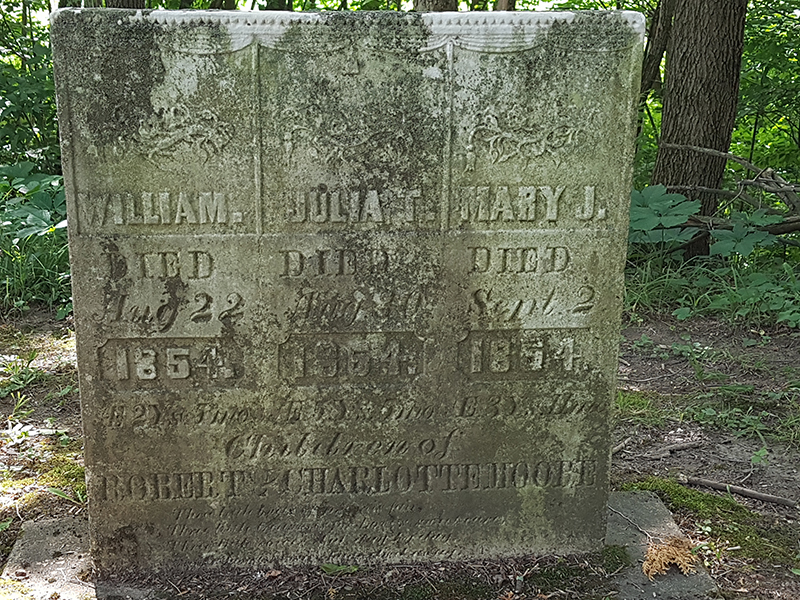

Robert Moore (1822-1893), an immigrant from Ireland, and Charlotte Hall (1828-1869) of St. Armand West were married in January 1848 by the Reverend Richard Whitwell. Their first daughter Julia Theresa was born on March 18, 1849. Their second daughter Mary Jane was born on September 18, 1851. And their son William was born on March 18, 1852. All three children were baptized by Reverend Whitwell on July 18, 1853. Just over a year later, he conducted their funerals. William died on August 21, 1854 and was buried the following morning. A week later, Julia Theresa died on August 30, 1854 and was buried the next day. On September 2nd at 3 o’clock in the morning, Reverend Whitwell recorded that “Mary Jane Moore died, age three, all but 13 days, and was buried at 4 p.m. the same day.”

The children were buried under one stone with an exact accounting of their time on earth in years, months and days. It was a conviction that God called peoples’ lives into being and who ultimately ended their time on Earth. Life, whether it was long or short, was God’s gift and every day was taken into account. People recorded their life in the full measure of time to acknowledge how much life had been given to them.

The great killers of children were infectious diseases. Respiratory ailments, which included influenza and pneumonia, proportionally struck younger children most heavily. Other diseases, including typhus, measles, diphtheria and whooping cough, were particularly hard on children. Whatever killed the Moore children in the summer of 1854 was swift and deadly. It is a common observation too that gastrointestinal diseases such as cholera and enteritis were particularly deadly for children during the heat of summer.

Some historians claim that the high incidence of childhood death created a lack of emotional bonding between parents and children. One study suggests that parents resisted making emotional connections until their children exhibited an ability to stay alive. Some parents even went so far as to delay naming babies until they were baptized. And the practice of giving the name of a deceased child to a new baby, are cited as practices which demonstrate this lack of connection. It is further argued that for farming families, children were a source of labour. If they died young, it was considered an economic loss rather than an emotional one.

These arguments hardly stand up next to the material evidence in museums and in personal collections of post-mortem photographs of children, curls of hair tucked into lockets, –treasured mementos packed away into boxes and the delicate imagery that grieving parents chose for the epithets on children’s gravestones. The gravestone of the Moore children is symbolic of the sorrow and love of heartbroken parents forced to say goodbye to beloved children. Engraved over each child’s name are the mourning symbols of wilted rosebuds symbolizing tender lives gone before they bloomed.

Robert and Charlotte had more children; welcoming five babies between 1855 and 1865. Charlotte died on December 2, 1869, less than four years after the birth of her last baby. She was buried next to her three oldest children. She had been given 41 years and three months. Robert died on February 9, 1893. He was given 70 years, four months and eight days.

Heather Darch

Sources:

Missisquoi Genealogy Transcriptions: Saint-Armand Ouest Church of England in Canada Folios 350-600 http://missisquoigenealogy2.blogspot.com/2016/02/saint-armand-ouest-church-of-england-in_27.html

Census returns for 1851: Stanbridge, Missisquoi County, Canada East (Quebec); Schedule: B; Roll: C_1128; Page: 179; Line: 13

Canadian History: Pre-Confederation by John Douglas Belshaw https://opentextbc.ca/preconfederation/chapter/12-2-childhood-in-a-dangerous-time/

Bones and burial registers: Infant mortality in a 19th-century cemetery from Upper Canada D. Ann Herring, Shelley Saunders, and Gerry Boyce https://orb.binghamton.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1228&context=neha

Fatal Years: Child Mortality in Late Nineteenth-Century America, Samuel H. Preston and Michael R. Haines: Princeton University Press 1991 https://www.nber.org/system/files/chapters/c11541/c11541.pdf