Jane Takes a Stand

Un texte de Heather Darch

Paru dans le numéro Été/Summer 2024

Publié le : 4 juin 2024

Dernière mise à jour : 4 juin 2024

Jane Freligh's story is a good reminder of how far we've come in terms of women's rights.

Jane Freligh (1803-1863) went to her grave an angry woman and rightly so. The only child of Richard Van Vliet Freligh (1781-1850) and Mary Marvin (1782-1841) of Frelighsburg, Quebec, Jane battled her formidable father and challenged a patriarchal court system.

Her life was not typical for a 19th century woman. She married a 26-year-old merchant named John Baker (1791-1847) when she was 14 years old for starters. Jane and John operated a community store before moving to Montreal. In the city, they operated the “Commercial Hotel” on rue St. Paul. Jane’s mother paid her daughter’s debts and expenses including travel to Frelighsburg, “costly dresses” and a piano forte. In 1841, Mrs. Freligh died. She willed her property to her husband “for his life only,” after which it was to pass to Jane.

Perhaps the loss of financial support from her mother and the resulting economic stress that followed, overwhelmed the marriage. By 1846, the couple had separated with Jane returning to her father’s household and John living in Dunham. The following year, John was killed accidentally. As he and Jane had no children, his property reverted to his heirs upon Jane’s death.

Until the middle of the 19th century, married men held a monopoly over property rights. Under the common law, a married woman could not enter into contracts, sue, or be sued. And her wages and personal property passed into her husband’s possession. He also gained the right to manage her real estate, and to control any rents or profits it produced. These laws were the cornerstones of a patriarchal social order and kept married women financially dependent. Quebec’s system of “partible inheritance,” meant that a widow was entitled to a half-share of any community property, but if her husband left no will, as in John Baker’s case, the remainder would be divided among his heirs and she would receive nothing.

In September 1849, Richard Freligh drew up a will that gave his daughter a comfortable and secure income for her life from the rents and revenues from his own properties. In November however, he changed his mind leaving Jane an annuity of only £75 on condition that she not take legal action against his executor. Freligh also claimed that his wife had no power to dispose of her own property and thereby prevented Jane from inheriting her mother’s wealth. Legally, he was correct.

He left his estate in the care of John Brush Seymour who had control of the assets for his life or until Jane Freligh produced an heir; something they both knew she could not do at her age. Jane did not take this lying down. Following her father’s death in 1850, she initiated a series of lawsuits against Seymour. In 1852, the verdict in Jane’s initial claim for unlawful seizure of the Freligh property went against her. She filed an appeal which again, was not upheld, but she continued to serve Seymour with notarized protests for being in arrears for her annual £75 payments, for taking personal property from the Freligh house and for non-payment of land taxes. She even laid a charge of assault and battery against him. It was all to no avail.

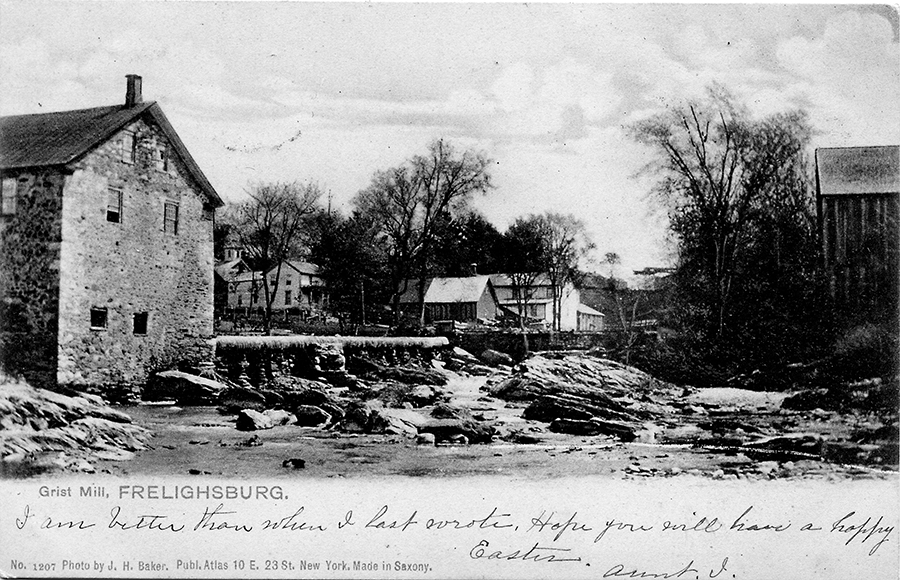

In 1862, Jane made her cousin Ebenezer Marvin her executor, leasing him “her property” and assigning him “her rights to her mother’s estate.” Even after Jane’s death, Richard Freligh’s will remained ensnared in lawsuits into the 1870s. Ultimately, under Seymour’s control, the Freligh lands suffered from waste and exploitation, and the Freligh mills, essential to the prosperity of the village, fell into disrepair.

The liberalization of family property rights came slowly in Quebec. Women campaigned for a better claim to family property and greater legal independence throughout the early 20th century. They gained improved inheritance rights in 1915, but political and church opposition hindered their efforts to achieve the vote until 1940. Radical changes to married women’s property rights, and the legal capacity to act for and represent themselves would have to wait for the social, religious, and governmental shifts caused by the Quiet Revolution.

Before she died on September 23, 1863, Jane purchased a gravestone for herself and had it inscribed with a Scriptural passage denouncing the “destroyers of mine heritage” and threatening “revenge” upon them (King James: Jeremiah 50:11). The Reverend James Reid silenced her final act of defiance and refused to allow the gravestone in his churchyard. To this day, her remains are unmarked by any monument.

Heather Darch

Sources:

Families and Property Rights in Canada, Chris Clarkson, Department of History, Okanagan College. https://opentextbc.ca/postconfederation/chapter/7-4-families-and-property-rights-in-canada/

Civil and parish registers (Drouin Collection), Quebec, Canada, 1621-1968 [on-line database], Seignory of Saint Armand and Frelighsburg.

Court of Appeals, Freligh vs. Seymour, July 10, 1855 Montreal Herald and Daily Commercial Gazette, July 20 1855, BAnQ https://numerique.banq.qc.ca/patrimoine/details/52327/3131878?docsearchtext=Jane%20Freligh

The Diary of a Country Clergyman 1848-1851, James Reid, edited by M.E. Reisner, McGill-Queen’s, 2000.

Image Source:

Freligh grist mill, 1905: Eastern Townships Resource Centre, ETRC-P058-010-05-002_009